Dinner with the husband, the shakes and metabolic flexibility

Have you ever experienced your hands starting to shake a little when you are hungry? When that happens, it’s time to get something to eat. Right?

Maybe.

Maybe not. This post is about that exact issue.

We had a great question this week from a member of The Academy.

About 3-4 hours after eating a meal, she can feel hunger setting in and her hands start to shake a little.

For her, this typically happens late afternoon / early evening. One option she has is to eat something (more on this later). But she doesn’t really want to do that. She likes having dinner with her husband and doesn’t want to mess that up!

She was following our recommendations and wondered if there was anything she could do.

Access and Metabolic Flexibility

There are many aspects to how and why your body gets hungry but since she was following our recommendations and experiencing less hunger overall, it didn’t sound like it was a food related issue. It sounded like an access and metabolic flexibility issue.

Here is a textbook definition of metabolic flexibility? In verbiage you might not find in an endocrinology journal, metabolic flexibility is defined as the ease in which your body can switch between burning carbohydrates and/or fats to produce energy. The less flexible your metabolism is, the harder it is to switch. Most people with poor metabolic flexibility are good at burning carbohydrates, which means burning fat is hard. This means that losing weight (specifically fat tissue) can be difficult.

When we eat a meal, the food provides a rush of energy that comes from the macronnutrients (carbohydrates, fats and proteins) and micronutrients (vitamins, minerals, etc…). Over time, this rush decreases and eventually returns to pre-meal levels. During this period of time, our body has access to a lot of potential energy. So we don’t feel hungry. But as the access to potential energy diminishes, we get closer to being hungry.

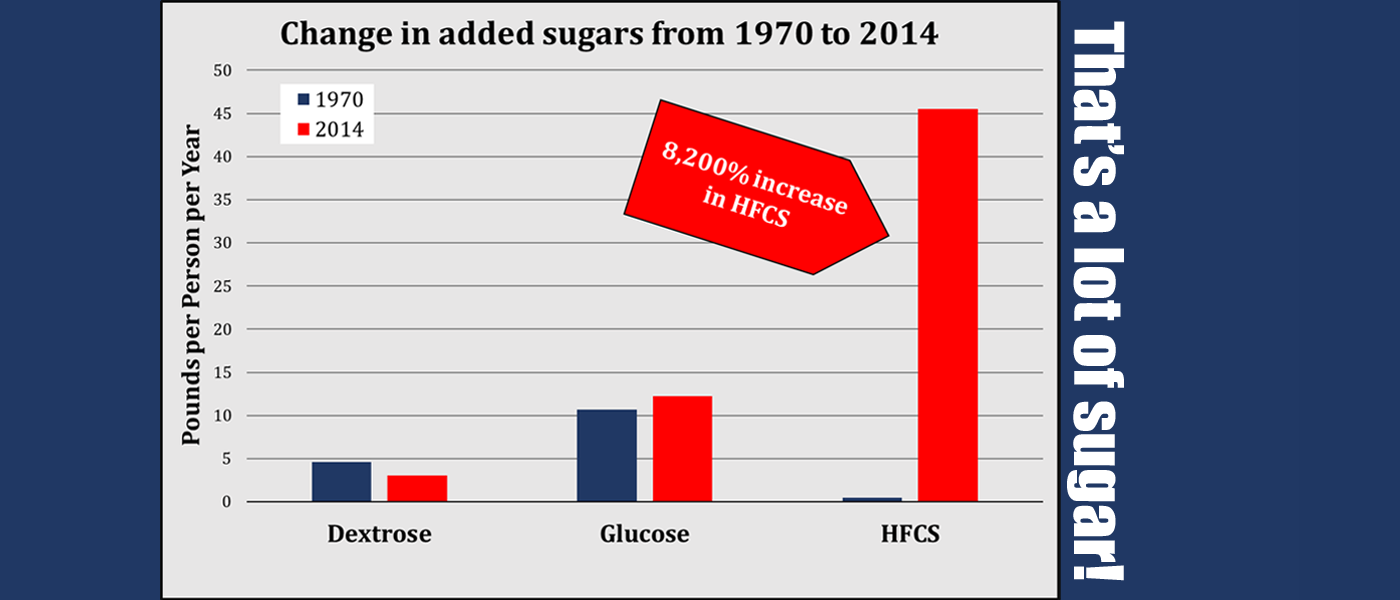

This is why metabolic flexibility and access to energy are tied together. Here is the situation for most adults: Your body has a lot of fat to lose but because your metabolic flexibility is poor, you can’t access it. This is the “access problem” we discuss in The Academy. When that rush of energy from the food you’ve eaten is gone, your body needs more. And if it can’t access fat stores, it sends hunger signals. Then you get hungry. Then you eat.

(This cycle starts with weight gain as a result of decreasing insulin sensitivity. As insulin sensitivity continues to decrease, pre-diabetes and then full-blown diabetes are on the horizon.)

Can we fix this problem?

Let’s return to our question. She was following our recommendations. In general, her hunger levels were better. This signals an improving metabolic flexibility. But, it wasn’t improved enough to keep her from getting the shakes or allowing her the ability to wait and have dinner with her husband.

To answer her question directly, the response was “Yes” there is something she can do!

At the beginning of this post, one of the things we mentioned that she could do was eat something. This would solve the problem because the “food rush” would provide a lot of potential energy, which would mean her body would stop trying to “access” the fat tissue. So eating food would fix it and eliminate the shakes.

Not practical for two reasons:

- The first is personal. She wants to have dinner with her husband. Eating would spoil that. So it’s not a good option.

- This one is from our perspective. Eating food when access is low only fixes the “lack of energy” problem and does nothing to address the access to energy problem. It just “kicks the can down the road.” She will eat. The shakes will stop. But as soon as the “rush” is over, she will be hungry again. Not a practical long term solution.

Ok, so what to do?

We have diagnosed this as an access and metabolic flexibility issue. From above, we noted these two things were tied together. If our diagnoses is accurate, then improving one should improve the other.

Earlier we defined poor metabolic flexibility. Optimal metabolic flexibility, conversely, means our body can easily switch between burning fats and carbohydrates to produce energy. If our metabolic flexibility is optimal, we can “access” the fat stores. This can eliminate the access problem and decrease hunger (and in this case, the shakes too!).

The prescription

We told her the following:

When the shakes set in and you are not ready to eat, take a walk.

Walking forces your body to burn fat, improving metabolic flexibility. In turn, this will help eliminate the access problem.

We suggested a 10-15 minute walk.

She went above and beyond.

She walked until the shakes disappeared.

It took 22 minutes!

Problem solved.

The shakes went away.

The access problem was gone.*

Most importantly, she was able to have dinner with her husband!

We are happy for her and glad to play a small role in her finding success!

*The access problem isn’t gone completely. But it is better. Most importantly, it’s better enough for her not to be so hungry that it might mess up dinner with her husband!

One Comment on “Dinner with the husband, the shakes and metabolic flexibility”